Proemion.

Immeasurable Earth!

Through the loud vast and populacy of Heaven,

Tempested with gold schools of ponderous orbs,

That cleav'st with deep-revolting harmonies

Passage perpetual, and behind thee draw'st

A furrow sweet, a cometary wake

Of trailing music! What large effluence,

Not sole the cloudy sighing of thy seas,

Nor thy blue-coifing air, encases thee

From prying of the stars, and the broad shafts

Of thrusting sunlight tempers? For, dropped near

From my remov-ed tour in the serene

Of utmost contemplation, I scent lives.

This is the efflux of thy rocks and fields,

And wind-cuffed forestage, and the souls of men,

And aura of all treaders over thee;

A sentient exhalation, wherein close

The odorous lives of many-throated flowers,

And each thing's mettle effused; that so thou wear'st,

Even like a breather on a frosty morn,

Thy proper suspiration. For I know,

Albeit, with custom-dulled perceivingness,

Nestled against thy breast, my sense not take

The breathings of thy nostrils, there's no tree,

No grain of dust, nor no cold-seeming stone,

But wears a fume of its circumfluous self.

Thine own life and the lives of all that live,

The issue of thy loins,

Is this thy gaberdine,

Wherein thou walkest through thy large demesne

And sphery pleasances,--

Amazing the unstal-ed eyes of Heaven,

And us that still a precious seeing have

Behind this dim and mortal jelly.

Ah!

If not in all too late and frozen a day

I come in rearward of the throats of song,

Unto the deaf sense of the ag-ed year

Singing with doom upon me; yet give heed!

One poet with sick pinion, that still feels

Breath through the Orient gateways closing fast,

Fast closing t'ward the undelighted night!

Anthem.

In nescientness, in nescientness,

Mother, we put these fleshly lendings on

Thou yield'st to thy poor children; took thy gift

Of life, which must, in all the after-days,

Be craved again with tears,--

With fresh and still-petitionary tears.

Being once bound thine almsmen for that gift,

We are bound to beggary, nor our own can call

The journal dole of customary life,

But after suit obsequious for't to thee.

Indeed this flesh, O Mother,

A beggar's gown, a client's badging,

We find, which from thy hands we simply took,

Nought dreaming of the after penury,

In nescientness.

In a little joy, in a little joy,

We wear awhile thy sore insignia,

Nor know thy heel o' the neck. O Mother! Mother!

Then what use knew I of thy solemn robes,

But as a child, to play with them? I bade thee

Leave thy great husbandries, thy grave designs,

Thy tedious state which irked my ignorant years,

Thy winter-watches, suckling of the grain,

Severe premeditation taciturn

Upon the brooded Summer, thy chill cares,

And all thy ministries majestical,

To sport with me, thy darling. Thought I not

Thou set'st thy seasons forth processional

To pamper me with pageant,--thou thyself

My fellow-gamester, appanage of mine arms?

Then what wild Dionysia I, young Bacchanal,

Danced in thy lap! Ah for thy gravity!

Then, O Earth, thou rang'st beneath me,

Rocked to Eastward, rocked to Westward,

Even with the shifted

Poise and footing of my thought!

I brake through thy doors of sunset,

Ran before the hooves of sunrise,

Shook thy matron tresses down in fancies

Wild and wilful

As a poet's hand could twine them;

Caught in my fantasy's crystal chalice

The Bow, as its cataract of colours

Plashed to thee downward;

Then when thy circuit swung to nightward,

Night the abhorr-ed, night was a new dawning,

Celestial dawning

Over the ultimate marges of the soul;

Dusk grew turbulent with fire before me,

And like a windy arras waved with dreams.

Sleep I took not for my bedfellow,

Who could waken

To a revel, an inexhaustible

Wassail of orgiac imageries;

Then while I wore thy sore insignia

In a little joy, O Earth, in a little joy;

Loving thy beauty in all creatures born of thee,

Children, and the sweet-essenced body of woman;

Feeling not yet upon my neck thy foot,

But breathing warm of thee as infants breathe

New from their mother's morning bosom. So I,

Risen from thee, restless winnower of the heaven,

Most Hermes-like, did keep

My vital and resilient path, and felt

The play of wings about my fledg-ed heel--

Sure on the verges of precipitous dream,

Swift in its springing

From jut to jut of inaccessible fancies,

In a little joy.

In a little thought, in a little thought,

We stand and eye thee in a grave dismay,

With sad and doubtful questioning, when first

Thou speak'st to us as men: like sons who hear

Newly their mother's history, unthought

Before, and say--'She is not as we dreamed:

Ah me! we are beguiled!' What art thou, then,

That art not our conceiving? Art thou not

Too old for thy young children? Or perchance,

Keep'st thou a youth perpetual-burnishable

Beyond thy sons decrepit? It is long

Since Time was first a fledgling;

Yet thou may'st be but as a pendant bulla

Against his stripling bosom swung. Alack!

For that we seem indeed

To have slipped the world's great leaping-time, and come

Upon thy pinched and dozing days: these weeds,

These corporal leavings, thou not cast'st us new,

Fresh from thy craftship, like the lilies' coats,

But foist'st us off

With hasty tarnished piecings negligent,

Snippets and waste

From old ancestral wearings,

That have seen sorrier usage; remainder-flesh

After our father's surfeits; nay with chinks,

Some of us, that if speech may have free leave

Our souls go out at elbows. We are sad

With more than our sires' heaviness, and with

More than their weakness weak; we shall not be

Mighty with all their mightiness, nor shall not

Rejoice with all their joy. Ay, Mother! Mother!

What is this Man, thy darling kissed and cuffed,

Thou lustingly engender'st,

To sweat, and make his brag, and rot,

Crowned with all honour and all shamefulness?

From nightly towers

He dogs the secret footsteps of the heavens,

Sifts in his hands the stars, weighs them as gold-dust,

And yet is he successive unto nothing

But patrimony of a little mould,

And entail of four planks. Thou hast made his mouth

Avid of all dominion and all mightiness,

All sorrow, all delight, all topless grandeurs,

All beauty, and all starry majesties,

And dim transtellar things;--even that it may,

Filled in the ending with a puff of dust,

Confess--'It is enough.' The world left empty

What that poor mouthful crams. His heart is builded

For pride, for potency, infinity,

All heights, all deeps, and all immensities,

Arrased with purple like the house of kings,--

To stall the grey-rat, and the carrion-worm

Statelily lodge. Mother of mysteries!

Sayer of dark sayings in a thousand tongues,

Who bringest forth no saying yet so dark

As we ourselves, thy darkest! We the young,

In a little thought, in a little thought,

At last confront thee, and ourselves in thee,

And wake disgarmented of glory: as one

On a mount standing, and against him stands,

On the mount adverse, crowned with westering rays,

The golden sun, and they two brotherly

Gaze each on each;

He faring down

To the dull vale, his Godhead peels from him

Till he can scarcely spurn the pebble--

For nothingness of new-found mortality--

That mutinies against his gall-ed foot.

Littly he sets him to the daily way,

With all around the valleys growing grave,

And known things changed and strange; but he holds on,

Though all the land of light be widow-ed,

In a little thought.

In a little strength, in a little strength,

We affront thy unveiled face intolerable,

Which yet we do sustain.

Though I the Orient never more shall feel

Break like a clash of cymbals, and my heart

Clang through my shaken body like a gong;

Nor ever more with spurted feet shall tread

I' the winepresses of song; nought's truly lost

That moulds to sprout forth gain: now I have on me

The high Phoebean priesthood, and that craves

An unrash utterance; not with flaunted hem

May the M

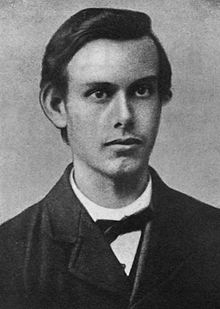

An Anthem Of Earth

Francis Thompson

(1)

Poem topics: breath, child, dream, father, feel, fire, history, house, light, lost, music, never, pride, purple, sick, sleep, sorrow, summer, sun, sunset, Print This Poem , Rhyme Scheme

Submit Spanish Translation

Submit German Translation

Submit French Translation

Write your comment about An Anthem Of Earth poem by Francis Thompson

Best Poems of Francis Thompson